The Statement

A meme shared on social media claims British statesman Sir Francis Bacon was the editor of the King James version of the Bible – adding that he was a Freemason who left masonic marks on the first edition.

One recent Facebook post including the meme has been shared by multiple users in Australia, while an older version has been shared more than 1000 times.

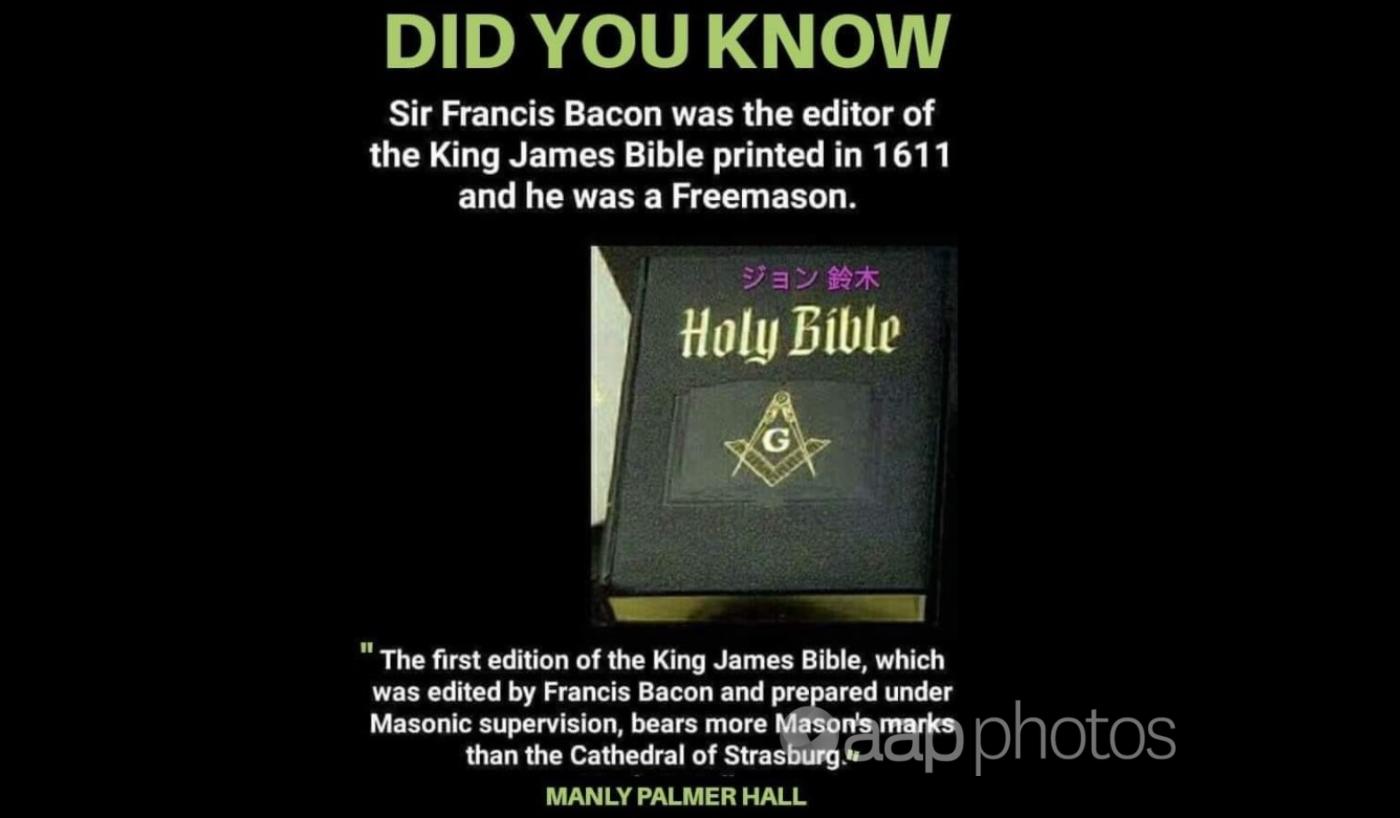

The meme includes an image of a book with the title “Holy Bible” and the masonic emblem on the cover. Text above the book image reads: “Did you know Sir Francis Bacon was the editor of the King James Bible printed in 1611 and he was a Freemason.”

Beneath the book is a quote attributed to Manly Palmer Hall: “The first edition of the King James Bible, which was edited by Francis Bacon and prepared under Masonic supervision, bears more Mason’s (sic) marks than the Cathedral of Strasburg (sic).”

The Analysis

The claim that Sir Francis Bacon edited a version of the King James Bible has been around for more than a century, however there is no evidence of his involvement in the substantial documentation surrounding the book’s lengthy translation and editing process.

Experts on Sir Francis and the King James Bible dismissed the suggestion that the statesman edited the Bible as baseless.

Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was a barrister later recognised for his writing and thought who served under King James I as solicitor general and later attorney general. He was knighted in 1603.

The process of formally translating what came to be known as the King James Bible began in 1604 under the supervision of the Archbishop of Canterbury, with the book intended to supersede several other English translations. These translations included one authorised by King Henry VIII and published in 1539. Until 1536, it had been forbidden to produce a Bible in English.

The King James Bible translation work was done by a committee of 47 scholars and clergymen, a list of whom appears here. Sir Francis is not included in the list.

Ample material has been preserved from the translation process. For example, the version of the Bible printed in 1611 contains 7342 margin notes by the translators, covering such things as obscure passages and the meanings of various biblical words. There is also a lengthy preface by the translators describing their work.

The purported link between Sir Francis and the King James Bible can be traced to the 1905 book The Mystery of Francis Bacon by William T. Smedley, which also includes conjecture that Sir Francis was the true author of Shakespeare’s plays.

However, in the book Smedley admits there is nothing concrete tying Sir Francis to the Bible, using this fact to fuel further speculation: “Is it not strange that there is no mention of any connection of Francis Bacon with this work?” (page 126)

Smedley then conjectures that based on the “homogeneity, breadth and vigour” of the rules governing the translation work they must have been authored by Sir Francis.

He also claims that only Sir Francis could have given the King James Bible its literary flourishes, adding that this was done between 1609 and 1610 when the work was supposedly in the king’s possession (page 128).

“It will eventually be proved that the whole scheme of the Authorised Version of the Bible was Francis Bacon’s,” Smedley adds. Nevertheless, the author notes in the book’s preface that its contents are only “extravagant theories”.

Canadian writer and mystic Manly Palmer Hall added to the conjecture around Sir Francis with a lecture published in 1929 in which he claimed, again without presenting evidence, that not only did Bacon edit the first edition of the King James Bible but he did so under Masonic supervision, adding that the text “bears more Mason’s (sic) marks than the Cathedral of Strasburg (sic)” (page 8). This line from the lecture is repeated in the meme.

It is the only reference to the Bible in the lecture, and Hall’s suggestion that Sir Francis was a Freemason appears equally unfounded. According to Freemasons’ own history, the first mention of the organisation – which is thought to be descended from guilds for stone masons who built Britain’s cathedrals and castles – was in 1646, 20 years after Sir Francis died.

A King James Bible scholar, emeritus professor David Norton of Victoria University in Wellington, told AAP FactCheck in an interview there was no direct evidence linking Sir Francis with the King James Bible among the substantial records that showed the long process that went into its publication.

He said the King James Bible was a “composite creation” which went through a series of revisions, adding the only reason people pushed for a link between it and Sir Francis was because “they believe in Bacon”.

“They are quite unaware of just how much evidence there is and what the real process of the making of the text was. And, of course, it was largely done before the King James translators got to it. It was a continuous writing process from essentially 1525 to 1611.”

The King James Version of the Bible partially relied on the earlier English-language Tyndale translation, published in 1526. The text was revised multiple times between this publication and the start of the formal King James translation process, which culminated in the 1611 version.

As for Smedley’s claim that Sir Francis may have accessed the Bible while it was in the king’s possession between 1609 and 1610, Prof Norton said there was no official account of King James receiving the work at this time.

David Simpson, a lecturer at DePaul University in Chicago and the author of the Francis Bacon entry in the peer-reviewed Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, said he was not aware of any responsible scholarship that supported the claim Sir Francis was involved in editing the King James Bible.

“That a rumour or surmise claiming that Bacon had a hand in the (King James Bible) arose and gained at least a few supporters isn’t surprising,” Dr Simpson told AAP FactCheck in an email.

“But such speculation, understandable given Bacon’s proximity to the throne and ever-willingness to please his majesty, seems to me almost on a par with his supposed authorship of Shakespeare’s plays. A proposition almost certainly false, but impossible to disprove.

“Members of the teams of scholars (the so-called translating committees) that worked on the Bible are pretty well documented, and they were all prominent figures of the day. Several of them were personally known to Bacon. Could he have offered a suggestion or two during the process of translation and final approval? Of course. But I am not aware of any evidence that he played an active role.”

The Verdict

There is no evidence to link Sir Francis Bacon with the editing or translation of the King James Bible. The claim appears to be based on long-standing conjecture made without any supporting proof.

Experts on the King James Bible and Sir Francis both point to the absence of evidence tying the lawyer to the work despite the existence of abundant historical material describing the translation and editing process.

False – Content that has no basis in fact.

* AAP FactCheck is an accredited member of the International Fact-Checking Network. To keep up with our latest fact checks, follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

All information, text and images included on the AAP Websites is for personal use only and may not be re-written, copied, re-sold or re-distributed, framed, linked, shared onto social media or otherwise used whether for compensation of any kind or not, unless you have the prior written permission of AAP. For more information, please refer to our standard terms and conditions.