Every week, the team at AAP FactCheck identifies dozens of pieces of potential misinformation – on social media and in the news media, and from private individuals, politicians and other public figures. While sorting fact from fiction is a full-time job for our journalists, you don’t need to work in the media or be trained in fact-checking to apply critical thinking to what you read and hear.

Here we outline the basic building blocks of our professional processes, along with some simple techniques and tips that everyone can apply. By pausing to ask yourself the three simple questions outlined below, you can begin to recognise false claims when they appear and help to limit the impact of misinformation.

The starting point with many of our fact-check articles is to work out where a claim originated. This is the purpose of the first of our three questions:

Who Made This Claim

Establishing who originally made a claim can reveal much about its reliability and purpose. While it is not always possible to pin down that source, considering this question is always a valuable exercise.

Is there any attribution?

Ask yourself, is a source making the statement themselves, or is it being attributed to someone or somewhere else? If it’s unclear where the information came from – for example, when someone starts with a vague “I read this on social media” or “I heard this from a friend” – that immediately sets off alarm bells.

In one case, AAP FactCheck examined a viral social media post outlining how an Australian motorist had nearly fallen victim to a gang using a “fake baby” as a lure. Our research showed versions of the same story had been around since at least 2009, with the locations and other details adjusted to suit the various countries where it was being shared. We discovered this by looking up some key terms using search engines and on social media.

Not all unsourced material is false

Professional fact-checkers are typically wary of any statements that are not backed up by a source. The refusal to provide a source is often a clear indication claims aren’t factual.

That is not to say all unsourced material is false. A corruption claim based on unnamed sources quoted by a journalist with a long history of exposing wrongdoing is more likely to be credible than one from an anonymous social media account with a history of posting about moon landing conspiracies.

What was really said?

If the claim is attributed to someone or somewhere else, our next step is to check if they actually said what is credited to them – and if they did, what was the context? Again, that usually means searching for keywords or whole quotes, but we may also contact the person or organisation at the centre of the claim.

Sometimes, statements are invented or misattributed online. This can happen when satirical material is passed off as fact, or when comments are falsely credited to respected sources in order to make a claim appear reliable. It’s also important to check the context in which a comment was made. In the case of a video, that may mean looking for an unedited version to see if context has been removed – for example, cutting off important qualifiers from a politician’s statement in order to change its meaning.

Check the source’s history

If we are able to establish the true source of a claim, we also look for any warning signs that they may be sharing information that is skewed to suit a particular agenda. Again, having a particular political or ideological bias doesn’t automatically make a source’s claims false, but it does help inform us about how content may be skewed or misrepresented to suit a viewpoint.

When the source of the claim is an article, there can be simple warning signs it’s not credible, like spelling mistakes, or opinions presented as facts. Many misinformation sources are designed to appear credible with names that closely resemble legitimate news or information sources; that’s our cue to look for more information by searching for the site’s name and seeing what other material is published there. Some initial background research helps give us an indication if a claim may be false before we move on to investigate the claim itself.

TIP: Looking up some or all of the exact wording of a claim in a search engine is a good first step to finding out about its origins and context.

What’s the evidence?

Once we have some idea of where a claim originated we start looking into what evidence there is to support it, and whether that evidence is sound. This is key, because sometimes claims will be based on nothing more than rumours, while even statements seemingly founded on hard facts can turn out to be a misinterpretation.

Find the original source – and check it

Looking for the evidence may mean trying to track down the original research or report that a claim is based on. This allows us to determine if it actually says what is being claimed, and whether context has been omitted. Information can be deliberately misrepresented or unintentionally misinterpreted to take on another meaning, or it can be misquoted or misread. In other cases, material is just simply made up.

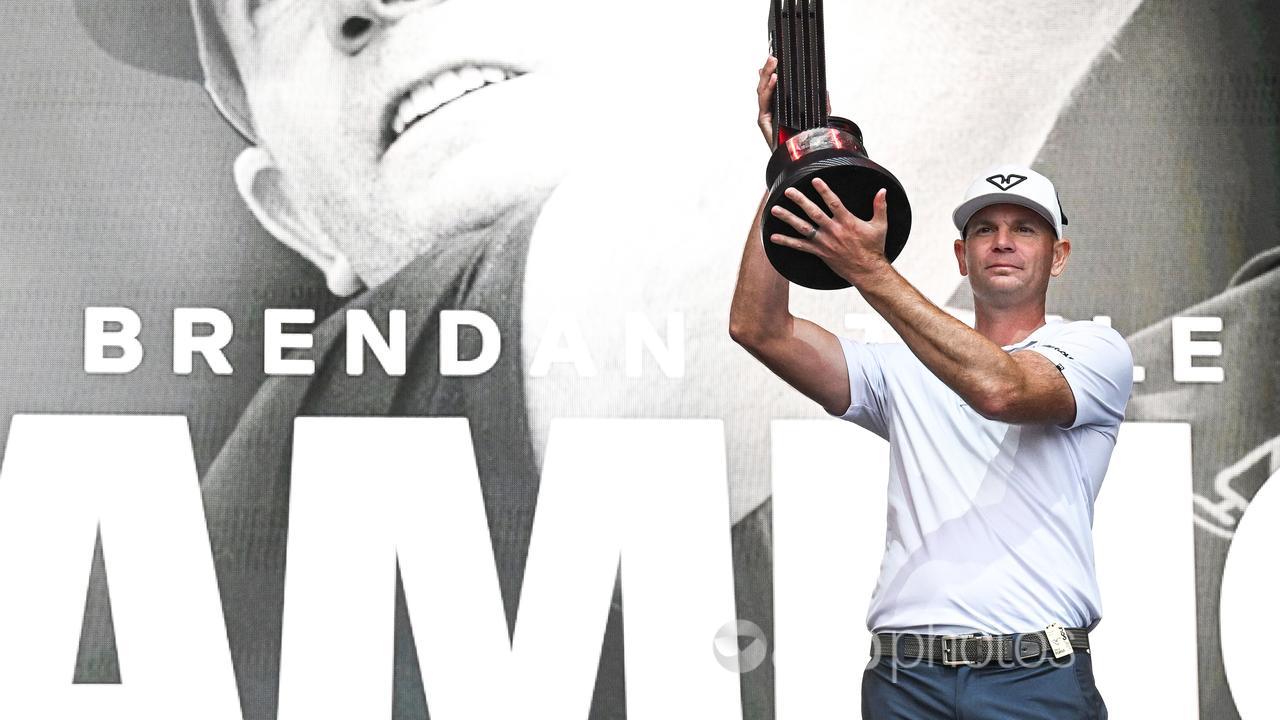

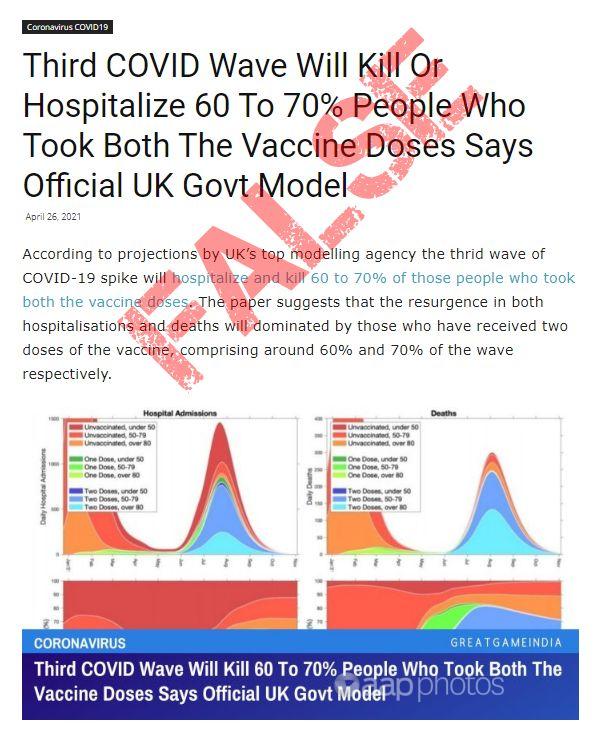

This article was shared by an Australian instagram account and seen more than 1500 times prior to being debunked AAP FactCheck.The Great Game India website, which claims to be a “journal on geopolitics and international relations”, publishes articles critical of COVID-19 vaccines and has also been fact-checked for spreading other misinformation.

Another step is to double-check any evidence against the most recent and reliable information; is material simply old and no longer directly relevant? If data is being used to support a claim, we look for the most recent data from a legitimate source, such as a government agency or recognised international body. In some cases, people may be relying on incorrect data to make a claim – or they may be confused by real data.

Even in cases where claims are backed up by media articles, we attempt to find the original material used as the basis of those news reports. A recognised media outlet is a more reliable source than a meme on social media, but the media can occasionally also get things wrong.

Tracing photos and videos

On social media, many claims are based on photos and videos. When investigating these, reverse image search tools are powerful aids. Sometimes, a reverse image search will reveal that an image is real but is being used in the wrong context – such as a photo of a crowd celebrating a football victory being passed off as a crowd of protestors.

In other cases, it may reveal that an image has been manipulated, with elements added or taken away. Videos can be tougher to investigate, but sometimes searching for the thumbnail image of a video will produce clues, or even taking screenshots of identifiable elements within the video – like faces and locations – and searching with these will reveal evidence that all is not as it seems.

Look for the first examples

When searching for either text or video, it is useful to look for the earliest examples on the internet because this often highlights how information or media has been altered over time. Some search engines allow for material to be sorted by date, while others give you the option to search only within a fixed period.

Another approach we sometimes use for images and videos is geolocation, which involves using resources such as online maps with street-level images to check if a location is actually where it is claimed to be. A video may take on very different meaning if it is filmed in Byron Bay rather than Bondi, for example. To do this, we look for visual clues in the material, like signs or unusual buildings, that can be cross-referenced with other images online.

Be wary of obscured material

Claims that have no evidence presented in support should be treated with caution, although these are also often the hardest to disprove. Any claims where potential sources of evidence or corroboration are obscured – for instance, where part of a document has been cut off in a screenshot; or names and locations have been left out – could indicate an attempt to present misinformation as fact.

TIP: Find the original research or article that a claim is based on – and make sure it actually says what is being presented as evidence.

What do trusted sources say?

Once we know what evidence there is to support a claim, we start weighing that up against other credible information. This can be the toughest part of the process, because often those making a statement will also present their information as coming from experts.

Check with other sources

The search of trusted sources can mean looking at media reports from recognised outlets, or searching resources like The Conversation or Meedan Health Desk for material written by academics and researchers on current topics of interest. Google’s Fact Check Explorer is also a good starting point as a claim may already be debunked by a recognised fact-checking organisation, ideally one accredited with the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) such as AAP FactCheck.

For many of our fact checks, we also contact experts directly to get them to comment on a claim or help us understand the available information. We always look for at least two independent sources that will help us reach a conclusion before we establish a verdict, and these sources should be clearly identifiable – either by name, or with a link when we are relying on a document.

Understanding research

When looking at claims that have a scientific element, such as health-related material, we often refer directly to research papers, although a lot of caution has to be taken in relying on any one paper’s conclusions as fact because often there are other studies that contradict its findings. As a starting point, we look at the most recent papers in reputable, peer-reviewed journals, relying wherever possible on meta analyses and systematic reviews from major institutions, such as reviews from the Cochrane Library.

When analysing material from experts, we also need to work out if their expertise is recognised; for example, are they affiliated with a major university or research institution? And is it in the most relevant field? While a virologist may know a lot about how viruses work, we would be more likely to consult an immunologist about the vaccines and other treatments used to combat them.

Not all experts are equal

Often, we’ll see misinformation being shared as authoritative because it comes from purported experts such as doctors or lawyers. But how much of an expert are they? A local solicitor is unlikely to have the same knowledge of constitutional law as an academic specialising in that field; a GP may not know the intricacies of a specialist field of medicine like cardiology. We also consider if their opinions run counter to the vast majority of other experts. That does not automatically make them wrong, but it does mean their claims should be critically assessed.

We also rely on statements and information provided by governments agencies or major non-government organisations like the World Health Organisation. While no organisation should be relied on as a single source of information, these bodies are generally reliable when their positions are weighed alongside information obtained from other trusted sources.

TIP: Dubious claims will often come from people who are presented as experts. Check that their expertise is relevant and recognised, and carefully weigh what they say against reputable sources.

Acknowledgements

This article was supported by Facebook.