Social media posts are questioning the authenticity of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, the founding document of the proposed Indigenous voice.

They claim it is a plagiarised copy of a “Zaire Statement from the Heart” and is being used to insert an African document into the Australian Constitution.

The claims are false. The Uluru Statement does incorporate words about spiritual sovereignty from an International Court of Justice hearing on Western Sahara.

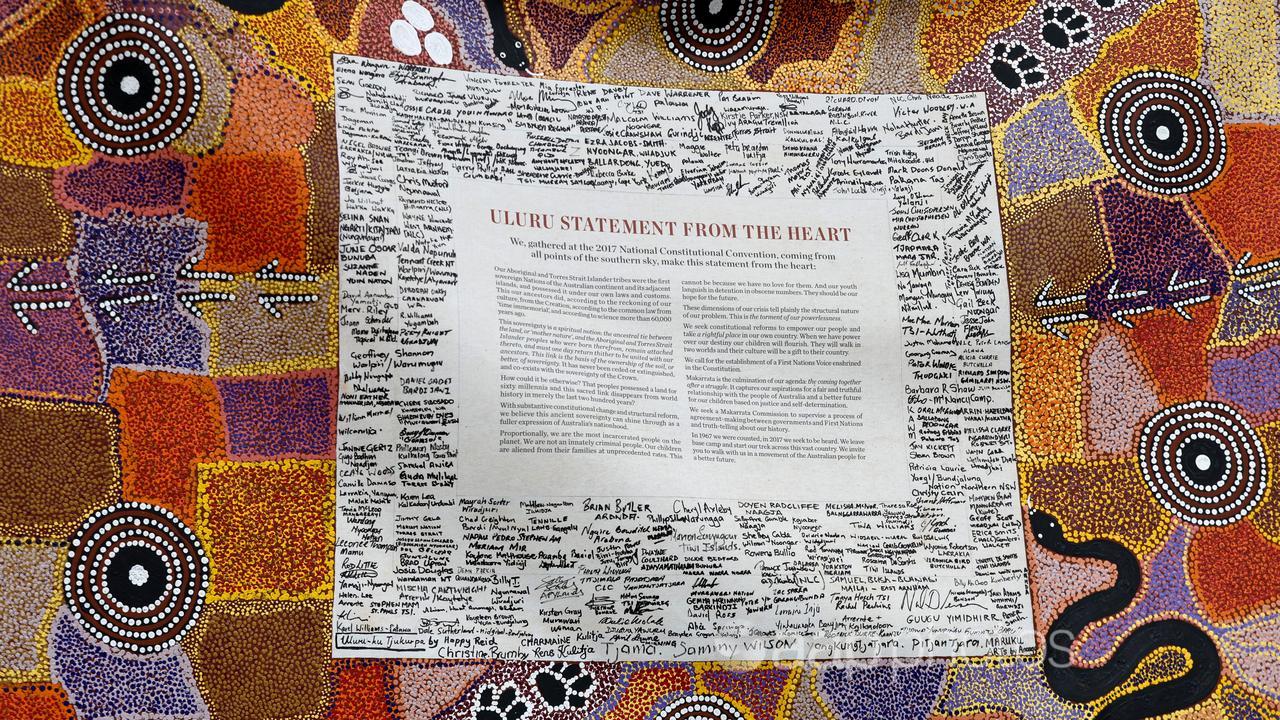

However, this is just one paragraph of the statement and it is correctly sourced in the Referendum Council’s final report. The Uluru Statement was written by delegates at the First Nations National Constitutional Convention in 2017.

Claims have been shared on social media following a report in The Australian by legal affairs contributor Chris Merritt, headed “Out of Africa: Uluru statement from the heart”.

Mr Merritt correctly states the document’s third paragraph, on sovereignty, is largely taken from a jurist in the International Court referring to matters in Africa.

However, numerous Facebook posts take this further with various misleading and false claims.

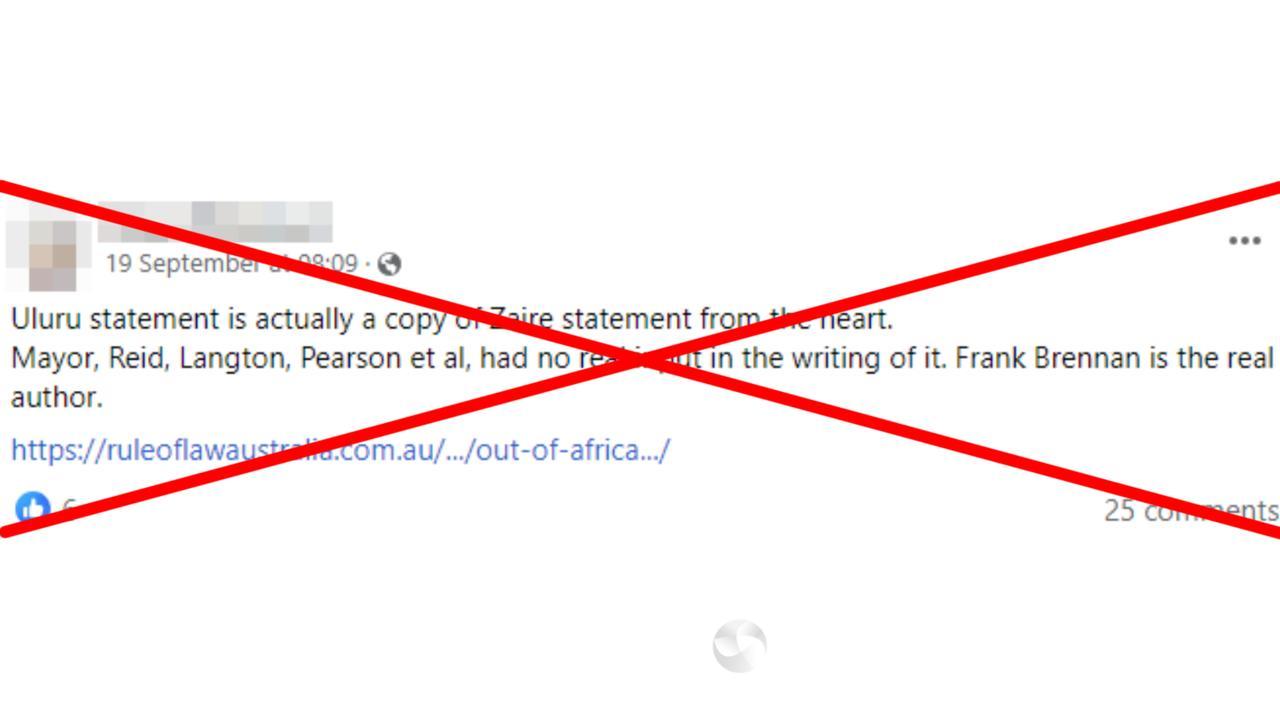

This Facebook post links to the article and claims: “Uluru statement is actually a copy of Zaire statement from the heart”.

Another Facebook post claims “a good portion” of the Uluru Statement was “plagiarised” and that “Albo wants a document from African nations to be included in the Australian Constitution.”

Another post states: “As we know the Uluru statement is a copy of the Zaire statement from Africa … Slightly modified to make it look Australian.”

This post claims the Uluru Statement “was written in 1979 in another country all but word for word”.

The claims are either false or misleading.

There is no such document as the “Zaire Statement from the Heart”.

Instead, the passage on spiritual sovereignty comes from Lebanese Judge Fouad Ammoun, speaking in a 1975 ruling of the International Court of Justice.

Judge Ammoun was summarising a submission by Zaire jurist Nicolas Bayona-Ba-Meya, that concerned the people of the Western Sahara.

However, it is not the first time the passage has been mentioned in connection with Indigenous issues in Australia.

It was also cited in the Mabo case in the High Court in 1992.

Claims that the passage has been plagiarised, stolen or passed off as original work are also false.

The Referendum Council’s final report, published just weeks after the Uluru Statement was written in 2017, correctly references the passage (PDF Page 2).

The spiritual sovereignty passage was outlined in an opinion piece by theologian Professor Mark Brett, which was published by the ABC in October 2022.

Professor Brett refers to the book Everything You Need to Know About the Uluru Statement from the Heart by Professor Megan Davis and Professor George Williams.

Professor Davis was co-chair of the Uluru Dialogues, a key voice in the process that resulted in the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and a member of the Referendum Council.

He notes that Prof Davis and Prof Williams acknowledge in their book that the wording around sovereignty substantially derives from the Western Sahara case.

In an email to AAP FactCheck, Prof Brett said the citation often appears in italics in published versions of the Uluru Statement.

“There has therefore been no attempt to obscure the chain of citations, but they have obviously been considered too academic for the voting public,” Prof Brett said.

Prof Davis said that the statement was intended to be in keeping with the style of early petitions from First Nations people to the Crown from the 1800s.

“In Commonwealth countries that have Indigenous populations, one-page petitions are a really common form of political participation and advocacy from First Nations people,” Prof Davis told AAP FactCheck in an email.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen an Aboriginal petition that has footnotes on it.”

Prof Davis said one of the most important aspects of the statement was conveying what it means to be Indigenous and what that notion of sovereignty is.

“We speak to a spiritual sovereignty partly because we discussed how everybody understands the physical land manifestation of the Mabo decision being land, but actually sovereignty is a spiritual thing,” she said.

“And so we referenced the Mabo case because of course people in attendance were Torres Strait Islanders or people involved in that litigation.

“Mabo is a big part of our discussions of where we’ve been recognised. And so we used the extract from Justice (Gerard) Brennan’s judgment that was drawn from the Western Sahara case as what we thought was the most famous exposition of what that means.

“It’s one of the most prominently cited, even in my work at the UN, when people are trying to explain Aboriginal culture and what sovereignty means.”

The Uluru Statement also features three other shorter quoted sections, again identified in the Referendum Council’s report (PDF Page 2).

Following Judge Ammoun’s words, the second sourced passage is at the end of paragraph seven.

It uses Australian anthropologist William Edward Hanley Stanner‘s phrase “the torment of powerlessness” to highlight structural issues facing Indigenous peoples.

This quote comes from his 1959 essay ‘Durmugam: A Nangiomeri’ in his book White Man Got No Dreaming (Page 93).

Paragraph eight uses the phrase “a rightful place” which is from a 1972 Gough Whitlam speech in which the former prime minister was advocating for Aboriginal land rights.

The final quoted phrase is taken from a passage on Makarrata, describing it as “the coming together after a struggle”.

It is a paraphrased definition from the late Dr Galarrwuy Yunupingu‘s essay Rom Watangu.

The Verdict

The claim the Uluru Statement from the Heart is a copy of the Zaire Statement from the Heart is false.

There is no such document as the Zaire Statement from the Heart.

The third paragraph of the Uluru Statement features a definition of spiritual sovereignty which is taken from proceedings of a 1975 case in the International Court of Justice.

The source of the quotation is provided in the Referendum Council’s final report.

False — The claim is inaccurate.

AAP FactCheck is an accredited member of the International Fact-Checking Network. To keep up with our latest fact checks, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

All information, text and images included on the AAP Websites is for personal use only and may not be re-written, copied, re-sold or re-distributed, framed, linked, shared onto social media or otherwise used whether for compensation of any kind or not, unless you have the prior written permission of AAP. For more information, please refer to our standard terms and conditions.