The Statement

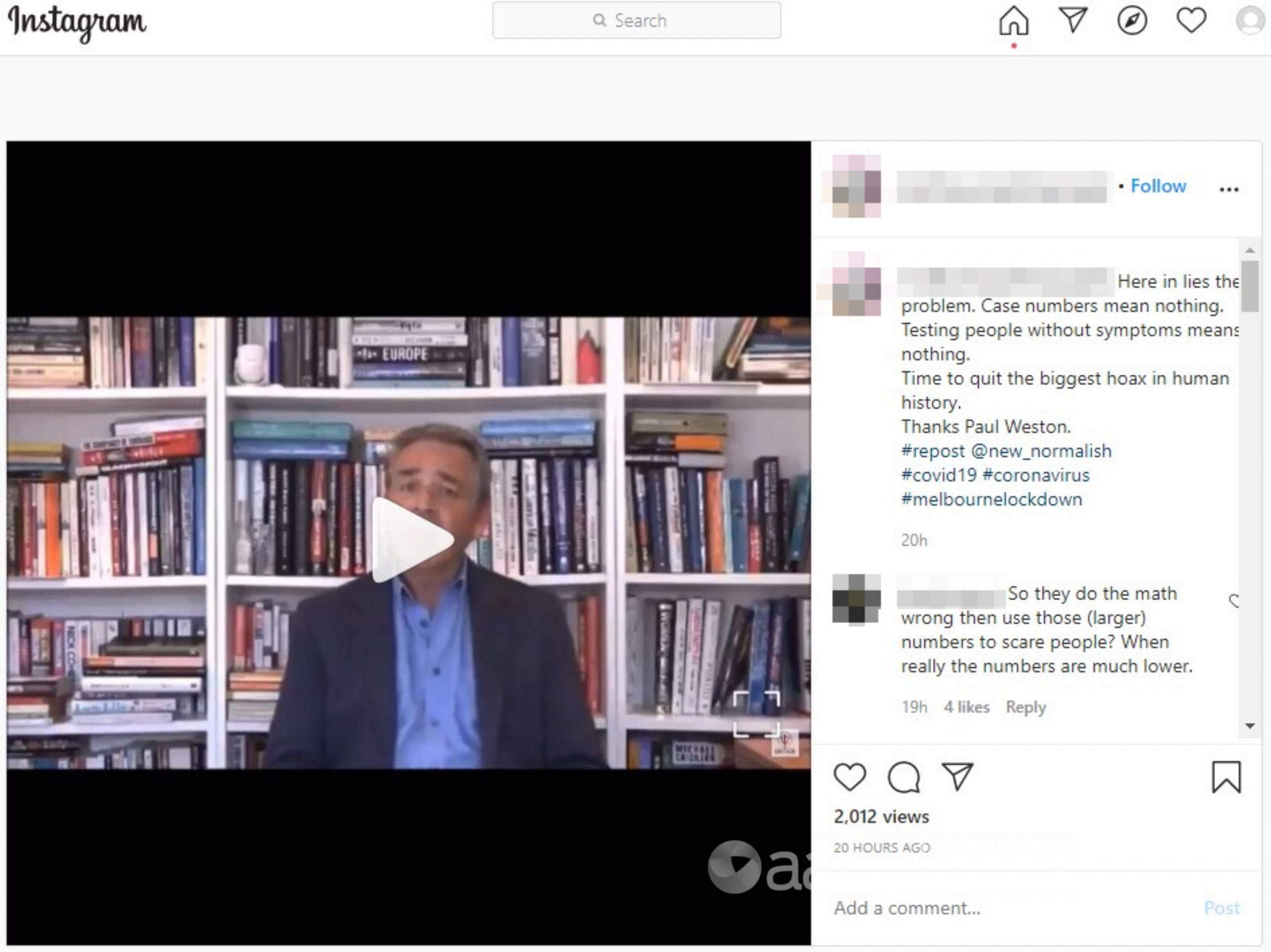

A social media post claims the high number of false-positive results from COVID-19 tests is rendering reported case numbers meaningless and the testing of asymptomatic patients useless.

The post by an Australian Instagram user features a short video clip of Paul Weston, a British former candidate for UKIP and Pegida UK, in which he says: “And they seem to think that if 10,000 tests returned 110 positives, and the false positive error percentage was one per cent, then the said one per cent applies to the 110 positive results therefore reducing the number to 109, a matter of little importance in the overall scheme of things.”

Mr Weston goes on to say, “But they’re wrong. (The false positive rate) applies to the 10,000 tested, and one per cent of 10,000 is 100, meaning the true positive number is only 10, not 109.”

The Instagram post’s caption reads, “Herein lies the problem. Case numbers mean nothing. Testing people without symptoms means nothing. Time to quit the biggest hoax in human history. Thanks Paul Weston.”

At the time of publication, the September 28 post had been viewed more than 2000 times and received more than 350 likes.

The Analysis

COVID-19 testing and its accuracy has been the subject of much debate in 2020. There have been testing issues in many countries, including the United States where the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) withdrew batches of testing kits earlier this year due to high rates of false positive tests.

False-positive results – a test showing that a person is infected when they are not – could occur in rapid-testing regimes if antibodies on a test strip also recognise antigens of viruses other than COVID-19, the World Health Organization said in April.

At the time, it recommended molecular (PCR tests), which require laboratory testing of samples but take longer to return results. In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration identifies PCR tests as the “gold standard” for COVID-19 detection, and state governments such as in Victoria deploy the molecular tests as the “test of choice”.

False positive rates vary depending on how and where people are tested. False positives are more likely in an area where the prevalence of COVID-19 is low, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) says.

A Public Health England research document, published in June, on the UK’s COVID-19 RT-PCR (reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction) testing program states that Britain’s false positive rate is unknown.

Meanwhile, a BBC report in September detailed the impact of false positives in order to address claims by commentators that they might be skewing COVID-19 figures.

Dr Paul Birrell, a statistician at the Medical Research Council’s Biostatistics Unit at the University of Cambridge told the BBC: “The false positive rate is not well understood and could potentially vary according to where and why the test is being taken. A figure of 0.5 per cent for the false positive rate is often assumed.”

Despite difficulties with assessing false positive rates, the numbers claimed in the video and their implications for the efficacy of coronavirus results bear no relationship to current COVID-19 testing information, experts told AAP FactCheck.

Professor Shaun Hendy from the University of Auckland, a physicist who led COVID-19 modelling efforts that informed the New Zealand government’s response to the pandemic, described the claims in the video included in the post as “highly misleading”.

“Firstly, the false positive rate is thought to be well below one per cent if the tests are conducted properly (more like 0.1 per cent),” Prof Hendy told AAP FactCheck in an email.

“Even then the argument made in the video would only apply if we were doing random testing of the population, which is not what is going on.

“In New Zealand, we are testing close contacts of other cases, workers at MIQ (managed isolation and quarantine) facilities, and people with symptoms.

“These groups are much more likely to have the disease than a random sample of the population, so the number of true positives will likely exceed false positives.”

University of Otago’s Professor David Murdoch, who specialises in epidemiology and infections, agreed, telling AAP FactCheck via email: “I’m not actually sure what a ‘false positive error percentage’ is, but we certainly wouldn’t use a test for which only 10 out of 110 positive results are truly positive.”

The video snippet included in the post is taken from a longer video featured on Mr Weston’s YouTube channel. In the video, he claims the true false positive rate for COVID-19 tests in the UK is 2.3 per cent – an apparent reference to a figure included in the Public Health England document (page 2).

The figure was drawn from a paper from three US academics, whose specialisations are in marine biology, plant biology and obstetrics/gynecology (page 10), who cited the false positives rates from PCR tests for other viruses, such as SARS, MERS and Zika (page 4).

Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, an epidemiologist from the University of Wollongong, said the testing regime for COVID-19 is not turning up the claimed number of false positive results – making it numerically impossible for a high percentage of tests to be returning incorrect readings.

For example, NSW conducted 68,421 reported tests in the seven days ending at 8pm on October 4, resulting in one positive case. At a false positive rate of one per cent, assuming no follow-up testing, there would have been 684 positive tests.

“As I explain in my blog, not only is the prevalence of COVID-19 (the proportion of people who actually have the disease) quite high in those tested (because they are a selected, symptomatic population), the specificity of PCR tests for COVID-19 is quite a bit higher than 99 per cent,” he told AAP FactCheck.

Test specificity is the measure of a medical test’s ability to correctly generate a negative result for people without COVID-19 – in other words, its ability to generate an accurate negative result.

“While no test is ever truly perfect, it is impossible for the specificity of the testing scheme in the UK to be lower than 99.92 per cent, and a reasonable estimate is somewhere around 99.995 per cent overall,” Mr Meyerowitz-Katz said.

Regarding the post’s claims false positives are inflating COVID-19 figures, Mr Meyerowitz-Katz said false negatives are more likely than false positives in the populations currently being tested.

“Ninety-nine per cent-plus of the positives in this population, given the true values, would be true positives, and in fact the main issue would be missing people who actually have the disease,” he said.

The Verdict

AAP FactCheck found the information in the Instagram post to be partly false. It is true there has been dispute about the efficacy of some COVID-19 tests, and there are limited studies that provide a clear figure for false positive rates.

However, the suggestion in the video that only 10 per cent of positive results may be “true positives” is inaccurate and the associated claim in the post that reported case numbers are meaningless is false. Experts say while there is always chance of COVID-19 tests produce false positives, that outcome occurs in significantly less than one per cent of examples.

Partly False – The content has some factual inaccuracies.

AAP FactCheck is an accredited member of the International Fact-Checking Network. If you would like to support our independent, fact-based journalism, you can make a contribution to AAP here.

All information, text and images included on the AAP Websites is for personal use only and may not be re-written, copied, re-sold or re-distributed, framed, linked, shared onto social media or otherwise used whether for compensation of any kind or not, unless you have the prior written permission of AAP. For more information, please refer to our standard terms and conditions.